IndiaSpend

26 October 2020

New Delhi: On June 19, 2020, traders P Jayaraj and his son J Bennicks were arrested and detained in Sathankulam police station in southern Tamil Nadu’s Thoothukudi district for allegedly violating COVID-19 lockdown rules. Three days later, Bennicks died in hospital, followed by Jayaraj’s death the next day. They had allegedly endured hours of beating and torture by police. On September 26, the Central Bureau of Investigation filed a chargesheet, booking nine Tamil Nadu police officials for the alleged murder of Jayaraj and Bennicks, among other charges.

This case is just one in an alleged pattern of endemic violence against persons in police custody that the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) has documented. Over 51 others have died in police custody in the seven months to July 2020, as IndiaSpend reported in July, based on NHRC data. By October 12, NHRC had registered another 16 such cases. Inadequate laws against torture and murder of persons in police custody, and the requirement of prior government sanction to prosecute the police under existing laws, have proved a hurdle in attaining justice, as we reported.

This article is the first of a two-part series analysing data on deaths in police custody in India over the past decade from the National Crime Records Bureau’s (NCRB) annual Crime in India (CII) reports, a compilation of such statistics provided by all states and union territories (UT) to the central home ministry, which maintains crime records. Unambiguous and standardised definitions could improve states/UTs’ reporting to the NCRB, marking a first step towards increased accountability for deaths in police custody. The second and concluding part of this series will examine statistics on compliance with accountability measures.

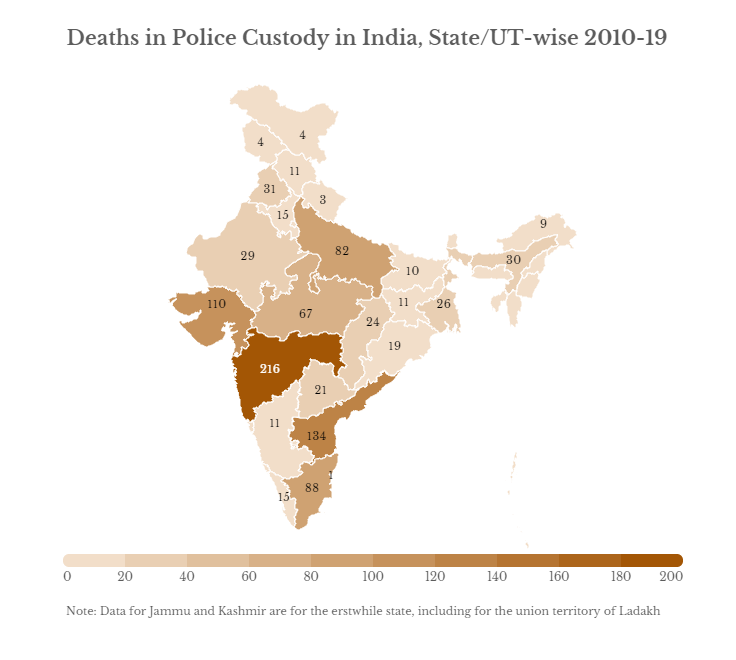

Just three states–Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat–accounted for almost half of deaths in police custody over the past 10 years. However, all such deaths may not be recorded as such, or reported to NHRC. There is a mismatch between the number of cases of such deaths between NCRB and NHRC data in 2019, which received more reports on deaths.

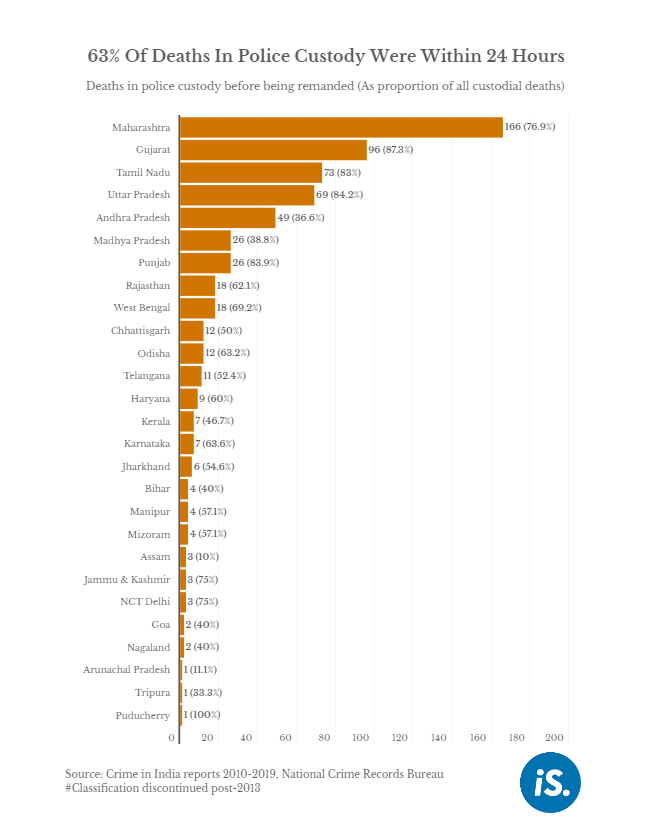

The cases documented by The National Campaign Against Torture (NCAT) were even more than the cases received by NHRC from states and UTs. A scan of media reports has uncovered more cases of death in police custody that are not reflected in reporting by some states to the NCRB. Uttar Pradesh has shown no police custody deaths in 2018 and 2019, although media reports show at least 10 such cases in this period and NCAT documented 14 in 2019 alone. The data also show that 63% of deaths in police custody occur within 24 hours of arrest, before they can be produced in court before a magistrate, in a Constitutional requirement aimed at preventing police excesses.

Under-reporting of deaths in police custody

Over 1,000 persons have died in police custody in the last 10 years, according to CII reports. More than one-fifth (21.5%) of these deaths were reported in Maharashtra, followed by Andhra Pradesh (13%) and Gujarat (11%). These three states together accounted for nearly half–460 of 1,004–of all police custody deaths reported in the past decade.

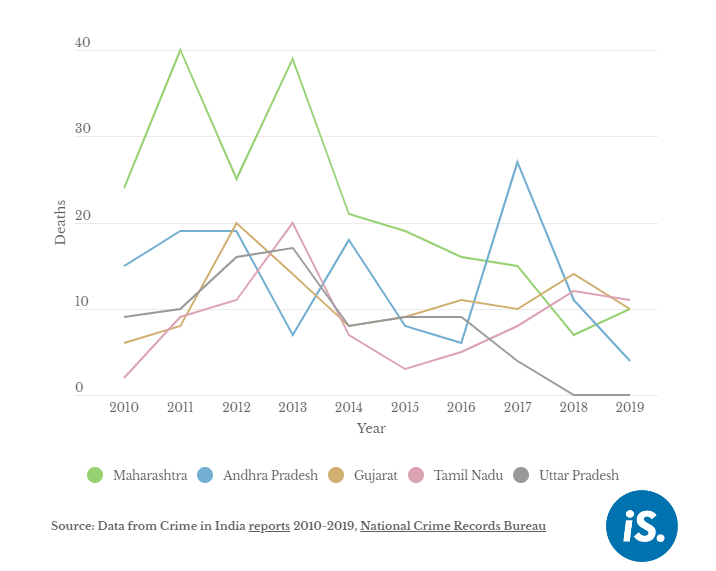

Of the five states reporting most deaths in police custody, Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Maharashtra show a sharp decline in the latter half of the decade. Of the 298 police custody deaths in these two states, 70% (209 deaths) were reported in the first five years. CII reports for 2018 and 2019 do not record any death in police custody from UP. Media reports, however, suggest at least 10 persons died in police custody in UP in this period.

These include: the father of a rape victim in Unnao district in April 2018; Govind in Sitapur in September 2018; Pavan Tiwari in Kanpur in November 2018; Balkishan in Amroha in December 2018; Ravindra Kumar in Kannauj in May 2019; Chottu alias Vinay in Mainpuri in July 2019; Shivam in Sonbhadra and Ram Avtar in Amethi in August 2019; and Satya Prakash Shukla in Amethi, Pradeep Tomar in Hapur and Deepak Mishra in Prayagraj in October 2019. In Ravindra Kumar’s case, NHRC had even issued a notice to the Director General of Police (DGP), UP. An extended scan of media articles may throw up more cases. NCAT documented 14 cases of death in police custody in UP in 2019, according to its India: Annual Report On Torture 2019–the highest among all states and UTs. UP’s official figures provided to NCRB, however, do not count any of these deaths.

NCRB shows 10 or fewer deaths in police custody in 18 states and UTs in the last 10 years, based on data received from states and UTs. Andaman & Nicobar showed only one death in police custody, while Sikkim, Chandigarh, Dadra & Nagar Haveli, Daman & Diu and Lakshadweep reported no such deaths over the last decade. These are India’s six least-populated states and union territories. No case in any of the six was documented by NCAT in 2019.

Two states with high population indicators, however, are also among states reporting 10 or fewer deaths in police custody to NCRB over the past decade. Delhi, the world’s second largest city by population, showed four such deaths in the last decade (0.4% of the total for India), fewer than Goa, Meghalaya and Nagaland (five cases and 0.5% of the total, each). In 2019, however, these states showed far fewer persons in police custody than Delhi. Goa reported arrests of 4,038 persons, Meghalaya 4,477 and Nagaland 1,972, according to CCI 2019. Delhi reported 11 times more than all three states combined, with a total of 126,138 arrests in 2019. A brief review of media reports shows at least four deaths in Delhi in 2019 alone. These include deaths of Balraj Singh in May, Govinda Yadav and Vipin aka Sumit Massey in June, and Mukesh Kumar in July. In Balraj Singh’s case too, the NHRC issued notice to the Delhi Police Commissioner. NCAT documented seven cases of death in police custody in Delhi in 2019 and none in Goa.

Bihar, India’s third largest state by population, shows 10 deaths over the past decade, behind Himachal Pradesh with 11. In 2019, Bihar saw arrests of 255,797 persons, more than 13 times the Himachal Pradesh total of 18,805. Bihar recorded one death in police custody in 2019. Reports of three such deaths, however, were found in a scan of Press Trust of India (PTI) archives alone, including two in Sitamarhi in March and one in Rohtas in August. NHRC also issued notice to the DGP, Bihar, in July 2019, after the death of a local politician in police custody in Nalanda. NCAT documented nine cases of death in police custody in Bihar in 2019 alone, behind only UP, Punjab (11) and Tamil Nadu (11), and just one in Himachal Pradesh.

Most deaths within 24 hours of arrest

On September 28, Rajpati Kushwaha, 45, died in Singhpur police station in Satna district, Madhya Pradesh, from a bullet fired from the service revolver of a police inspector, PTI reported. He had been “picked up” by police the previous night in connection with a theft case.

Every arrested person has a constitutional right to be produced before a magistrate within 24 hours, as said above. Most deaths over the past decade, however, took place like Kushwaha’s, before this first oversight could kick in, NCRB data show.

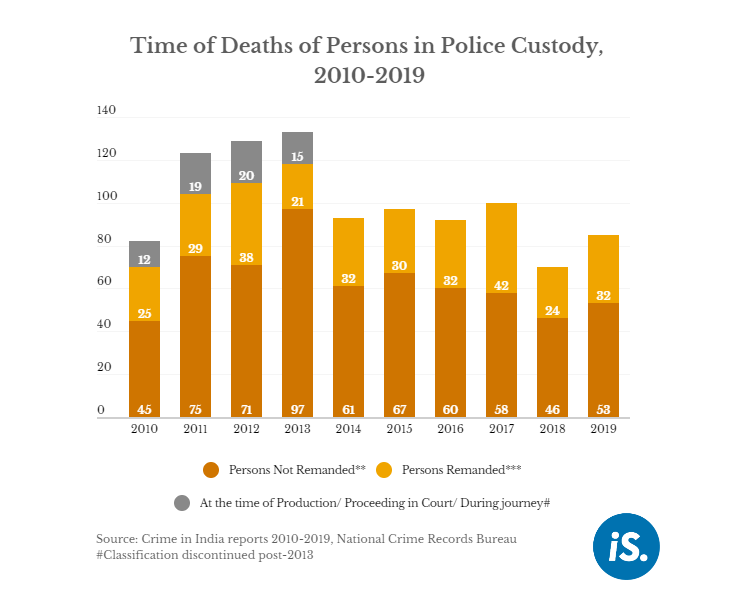

Of the 1,004 deaths in police custody in the last 10 years recorded in CII reports, a majority of persons–63%–died within 24 hours of being arrested by the police (‘Person not remanded’ in table below). All told, 633 persons died before being produced in front of magistrate’s courts, as prescribed by Section 57 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973.

In Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Punjab and Maharashtra, more than three-fourths of deaths reported in police custody occurred within 24 hours of arrest. As many as 87% of such deaths in Gujarat were reported within 24 hours of arrest. In Tamil Nadu, such instances increased as the decade wore on. In the last six years (2014-2019), 44 of 46 (96%) persons reported to have died in police custody in Tamil Nadu died within 24 hours of arrest.

In 2019, in line with the pattern over the last decade, 62% of the people reported to have died in police custody had died within 24 hours. In 2013, this figure was 73%, the highest over the decade.

Arrested persons who died in police custody after being produced before courts as per Section 167, CrPC accounted for less than a third of cases.

From 2010-2013, 66 deaths took place while travelling to court or proceedings in court or journey connected with investigation. Around 86% (57) of these deaths occurred in five states–Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh.

After 2013, the NCRB discontinued reporting deaths in police custody “at the time of production/proceedings in court/ Journey Connected with Investigation”. This eliminated the data point that reveals how many arrested persons die while being transported by the police to court and for investigation.

The death of Kanpur gangster Vikas Dubey on July 10, 2020, while in custody of UP Police, as well as the deaths of four rape accused in Hyderabad on December 6, 2019, in the custody of Telangana Police, are instances of cases that would have been included in this classification had it not been discontinued.

Mismatch with NHRC, civil society data

NCRB’s CII reports can indicate the extent of torture in police custody across India, only if states/UTs provide complete data to it. For instance, West Bengal did not submit data for 2019 in time, due to which NCRB repeated its data from 2018 in its report, the CII 2019 report said.

The NCRB depends on state governments and UT administrations to report deaths in police custody, which they may not do. Analysis showed differences between NCRB and NHRC data on deaths in police custody.

Every death in police custody is to be reported by district magistrates and superintendents of police to the NHRC secretary general within 24 hours, as per NHRC guidelines on custodial death. Every month, the NHRC publishes statistics on deaths in police custody, based on reporting from states and complaints made directly with NHRC.

NCRB recorded 85 cases of death in police custody in 2019. NHRC, however, registered 117 cases of police custody deaths in the same year–38% more. In August 2018, the home ministry informed Parliament that NHRC had found “no significant difference between their data and that of NCRB”. It added, however, that “NHRC had noticed that there was some under reporting to NHRC from the States of Haryana and Madhya Pradesh and the matter has been taken up with respective State Governments as also with NCRB for re-conciliation and coordination”. The NHRC, later in 2018, had also written to the Odisha Chief Secretary seeking an explanation for under-reporting of police custody death data to NCRB by the state.

The difference can be attributed to under-reporting by states and UTs, as seen above from media reports, and the absence of standard definitions in cases of deaths in custody other than that of the police, but possibly caused due to violence in police custody. (Read about the distinction between police and judicial custody here.)

Civil society organisations put the number of cases even higher. Deaths of 124 persons in police custody in India in 2019 were documented by National Campaign Against Torture (NCAT) in its India: Annual Report On Torture 2019. Three-fourths of these deaths were due to torture or foul play by police, relatives and local residents alleged, the report noted.

| Deaths In Police Custody In 2019 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sources | NCRB’s Crime in India, 2019 | NHRC | NCAT’s compilation |

| Deaths in Police Custody | 85 | 117 | 124 |

Sources: Crime in India report, 2019, National Crime Records Bureau; National Human Rights Commission; National Campaign Against Torture

Ambiguous classifications and definitions

The CII reports do not lay down clearly what deaths are included in ‘deaths in police custody’.

The Supreme Court of India has defined what being in police custody means, expanding it from the confines of a police station or vehicle, to whenever a person’s movements are constrained by the police. This leaves room for different locations in which a person can be in police custody, and various circumstances in which they could be harmed while in custody. Cases of death of persons ‘in remand’ in CII reports could include those who may have died immediately after being sent to judicial custody, or while being taken to jail in the custody of the police, but this is not certain in the absence of clear classification post-2014.

There is also a lack of clarity about categorisation of death of a person immediately after the completion of their police custody. A clearly defined fixed time frame for ‘immediate‘ is required. In the absence of these clear definitions by a competent Indian authority, ambiguities in assigning responsibility for deaths of arrested persons will persist. Other countries have developed frameworks to clearly indicate which deaths are included and excluded. For instance, the United Kingdom’s Independent Office for Police Conduct issued guidance in 2018 detailing definition of “deaths in or following police custody” and explained the rationale for why different scenarios were included.

(Raja Bagga works for the police reforms programme at the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative and can be reached at raja@humanrightsinitiative.org. Devika Prasad, head, police reforms programme at CHRI, contributed to this article.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.