The Pioneer

14 July 2020

The only way to prevent and eliminate custodial deaths is to make the senior police officers directly accountable whenever such incidents occur in police stations under their jurisdiction

On June 26, three days after the father-son duo, P Jayaraj and Bennix, died after being brutally tortured in police custody in Sathankulam in Tamil Nadu (TN), a non-governmental organisation (NGO), the National Campaign Against Torture (NCAT), brought out its annual report for 2019. It revealed that a total of 1,731 people had died in custody in India during 2019, which is a whopping five deaths every day. A majority of these deaths, 1,606, happened in judicial custody and 125 in police custody, like the present ones.

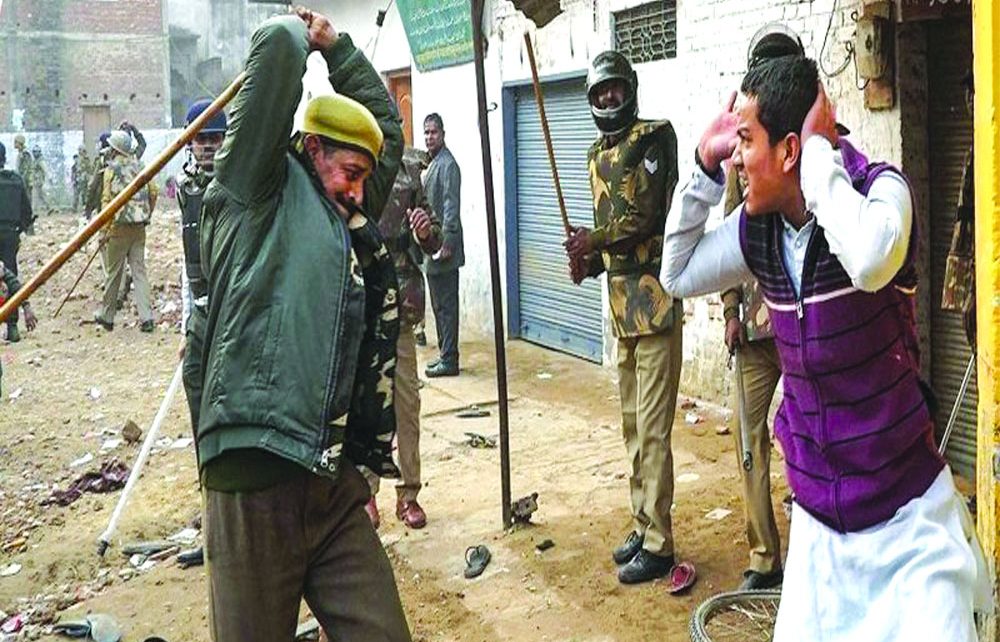

The methods of torture used, like driving nails in the body or rods through the private parts, burning or other atrocious methods of torment would put even the medieval Inquisition to shame. It also highlighted that 75 per cent of the victims belonged to poor and marginalised communities or minorities, who have practically no access to legal remedies.

Investigations into these cases almost always lead to closure without any culpability being established and instances when someone is actually punished for the deaths are extremely rare. The deaths are attributed to either “natural causes” like prior illnesses and “injuries sustained prior to police custody” or “unnatural causes” like suicides. As per the statistics provided in the National Crime Records Bureau’s (NCRB’s) latest report on Crimes in India, 2018, in cases of 70 deaths in police custody, not even a single arrest was made, let alone conviction.

As per the Constitution of the country, policemen are public servants and a police station is considered a public property. Therefore, the duty and the behaviour of a policeman must conform to the country’s law, respect basic human freedom and obey as well as maintain law and order. However, the ground reality is far from this and time and again, policemen are involved in custodial violence and deaths.

To prevent custodial violence, elaborate guidelines to be followed in all cases of arrest or detention were prescribed by the Supreme Court in its 1996 verdict in the DK Basu vs State of West Bengal case, and subsequent judgments made in 2001 and 2015. These guidelines are observed only in their breach. Any inquiry by a human rights group through the Right to Information (RTI) Act or otherwise almost always draws a blank, with the information sought being “unavailable.”

In 2015, Section 176 (1) of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) was amended by replacing the earlier provision of inquiry by an Executive Magistrate with that by a Judicial Magistrate. This also is rarely conducted or conducted mechanically, only to satisfy the formalities. Only after the nationwide outrage after the Sathankulam incident, the Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court ordered a Judicial Magistrate’s inquiry into the incident and the five policemen were arrested in the case and transferred to the Madurai Central Jail from Tuticorin. Now, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) is probing the case.

In 2006, the apex court also directed that every State should have a Police Complaints Authority where anyone can lodge a complaint against policemen. Only a few States such as Kerala, Jharkhand, Haryana, Punjab and Maharashtra have set up the authority. But that has not prevented custodial deaths — Punjab, along with Uttar Pradesh (UP) and TN, recorded the highest number of deaths in police custody in 2019.

In 1994, in its 152nd report, the Law Commission had remarked that despite all legal and constitutional safeguards, “The growing incidence of custodial torture and deaths has become a disturbing factor in society and the gory tales of dehumanising torture, assault and deaths in the custody of police are being reported almost in every morning newspaper.” It observed that inquiries are conducted as a mere formality. Even more than 25 years later, things have not changed one bit on the ground. At best a monetary compensation is offered by the State. In the TN case, the State Government announced a compensation of Rs 20 lakh and the DMK’s Thoothukudi MP Kanimozhi declared a compensation of Rs 25 lakh for the bereaved family. However, this is not enough to make up for the loss of the main bread-winners of the family, which is not backing off and is seeking justice for the two men.

But in other cases, money usually silences the victims’ families, who mostly come from poor and marginalised backgrounds. In a rarest of the rare instances of its kind, for torturing a man to death in custody in 2006, a Delhi Sessions Court sentenced five UP policemen to 10 years of rigorous imprisonment in 2019. They had manipulated records to erase all evidence of custodial death before closing the case as a suicide.

The judge very aptly remarked on that occasion, “One of the reasons for custodial death is that the police feel that they have the power to manipulate evidence as the investigation is their prerogative. And with such manipulated evidence, they can bury the truth. They are confident that they will not be held accountable even if the victim dies in custody and even if the truth is revealed.” The fact remains that the inter-departmental solidarity will always tend to shield the perpetrators and give them protection in such cases. This gives them a sense of invincibility and gives them a licence to kill with impunity. The failure of the judicial system to bring the culprits to book follows as a natural corollary to the failure to fix accountability.

Indeed custodial torture should have no place in a civilised society but in our criminal justice system, it has been institutionalised. Torture and extra-judicial killings deem even to have acquired some legitimacy in the eyes of the public, as shown in the Hyderabad killing of four gang-rape accused by the policemen last December.

Whitewashing and covering up are the norms. After the Sathankulam incident, the top police brass was busy trying to cover up the case, citing esoteric procedures. The Judicial Magistrate inquiring into the murders was intimidated by three police officers, the crucial CCTV footage in the police station was erased and the woman constable, who courageously deposed against her colleagues and whose testimony finally nailed the murderers, was under constant threats and intimidation.

It was only the widespread public anger that forced the TN Government to arrest the five culprits, transfer the probe to the CBI and take the extraordinary step of transferring the Santhakulam Superintendent of Police to keep him under “compulsory wait” at the DGP office, probably the first ever. This, however, is no punishment, and once the public anger subsides, it will be business as usual.

In the US, the 46-year-old George Floyd had struggled for nine minutes under the knee of the white Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin, beseeching and begging for his life — “I can’t breathe.” Actually the chokehold has been suffocating the US justice delivery system for the Blacks for a long time but the incident triggered the pent-up anger and resentment, leading to protests and violence that spread like wildfire across the globe.

The ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement upset many Indians, too, who voiced their anger on the social media. But no protests against police atrocities have erupted across our cities after the deaths of P Jayaraj and Bennix. Either we are too scared or we just don’t care if cops go on a rampage. In the US, it has led to calls for police reforms and defunding the police. Use of chokeholds has been banned and it has also forced US President Donald Trump to issue an executive order for establishing a database to track police officers with a history of “excessive use-of-force complaints” in their records. Derek Chauvin had a history of using excessive force; such persons in future would carry it in their service records. This will likely serve as an effective deterrent.

The 18th Century French political philosopher Montesquieu wrote in his magnum opus, The Spirit of Laws, “There is no greater tyranny than that which is perpetrated under the shield of the law and in the name of justice.”

If we aspire to have some semblance of a civilised society, we must eradicate such tyranny. The only way to prevent and eliminate custodial deaths is to make the senior police officers directly accountable whenever such incidents occur in police stations under their jurisdictions. A death should be reflected in their service records and should carry a negative weightage in their promotions and postings. Senior police officers alone can prevent this, and only when they are made directly accountable will this scourge stop.

(The writer is a former Director General at the Office of the CAG of India and an academic.)